Norman Wells

Tłegǫ́hłı̨

The Town I Live In

My town Norman Wells lying in the valley between two mountain ranges. A wide, fast river, passing by the town. Our main transportation source in the summer. The summers are hot with the sun never setting. Hot, sizzling, dry heat Everywhere. Cold, blinding winters. Rushing winds everywhere. The northern lights sparkling like diamonds or dancing fireflies.

by John Bounds,13 years Norman Wells, 2000

Both the English and Dene names for Norman Wells refer to the oil on which the local economy is based. The existence of oil seepages was known by Dene people passing through the area, and explorer Alexander Mackenzie noted these in the 18th century. But it wasn't until 1919 that the first well, called "Discover." was drilled. And it wasn't until the opening of the uranium mine at Port Radium in 1932 that it became economically feasible to commence production. Norman Wells benefited from a second boom during World War II with the construction of the Canol pipeline to Whitehorse, but this was short-lived.

After the war, the size of the Norman Wells operation followed expansion of the oil and gas industry. In the mid-1980's, a pipeline was completed to Zama, Alberta. The population grew to a peak of about 3,000, the majority of whom were fortune-seekers from the south. With highly skilled, high wage jobs available, Norman Wells still has one of the highest average income populations in Canada.

The town became a regional hub with jet service north and south and a number of regional government offices. A strong Métis community also took root in Norman Wells, and increasing numbers of Dene people from the Sahtu communities now are finding seasonal employment there.

Oil reserves at Norman Wells are now in decline, and the population recently shrunk to less than half its earlier size. However, development of adventure tourism diversified the economy, and oil and gas developments elsewhere in the region are providing new opportunities for growth.

Historic Centre in Norman Wells Drilling Islands on the Mackeinzie River

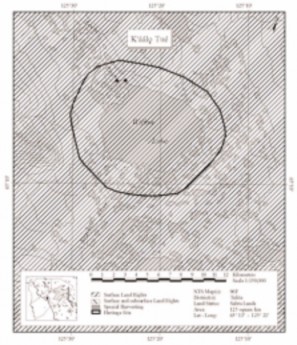

K’áálǫ Délı̨nę Délı̨nę Tué / Willow Lake (Brackett Lake)

Willow Lake (called Brackett Lake on the official maps) is the site of an important seasonal camp, and is considered the home of the K’áálǫ Got’ine, or ‘Willow Lake People’. The area is important for hunting, fishing and trapping, and the lake and wetlands nearby support large populations of animals. A small community of several cabins is located on the lake. The oral tradition records many stories, which tell of the importance of this lake. In the story below, Yamoria, who was pursued by an elderly couple and his angry father-in-law, uses Willow Lake to avoid capture. In so doing he creates an important subsistence fishery on the lake [adapted from Hanks 1993:39-41]

Sahtu Heritage Places and Sites Joint Working Group, Rakekée Gok’é Godi: Places We Take Care Of.

Yamǫga Fee / “Yamoga Rock”

A large, bedrock ridge visible on the flight path from Good Hope to Norman Wells, Yamǫga Fee is an important sacred site to the people of the region. The story of this site tells of the battle between a culture-hero named Yamǫga and his enemy Konadí. After skirmishing over an entire winter, they met in a final battle at Yamǫga Fee. An elder from Fort Good Hope recounts the story:

After Konadí survived the winter, he managed to gather a group of people again and they started their hunt for Yamǫga again around Nofakóde Tué. They were on a creek when they found a wood chip floating in the water. They followed this creek called Táwalin Niline, until they came to a dwelling where they found a man by himself. Konadí already knew that he was Yamǫga's nephew. He told him "you’re as good as dead unless your uncle gives up before he comes back to camp." The boy told them that his uncle would yell 'Sahæá' (meaning 'sebá', 'my nephew'). They asked him what signal he would give in return. They boy said "wihoo". If the reply were different then Yamôga would know that something was wrong. After the boy had taught them this they killed him. They had a youth with them who they told to be ready with the reply to Yamǫga's signal. They left this boy in camp and his group followed Yamôga and his group. They made sure they left no tracks that could be noticed and they hid along both sides of the trail they expected Yamôga and his men were using to hunt.

It must have been warm during the day for Yamǫga's group because their footwear was wet, but towards evening their footwear froze. Yamôga told his men to change their footwear but it was said that they didn't. If they had done this, they would be in a better way to defend themselves against Konadí's attack.

Yamǫga gave his signal from atop that mountain, "Sahɂá!” The boy at the camp without thinking gave the wrong signal. Yamǫga knew there was trouble. He yelled at his men and told them. They should have listened to him when he asked them to change to dry shoes. Yamǫga had a skinned and deboned beaver that he had frozen into the shape of a club. He fought with this but he was wounded badly. He went to the highest point of that cliff. Konadí and his men didn't want to leave him because he was wounded and there may be a chance that he would survive. They sent two young men after him and told them to throw Yamǫga off the cliff if they found him. The two young men did find him and tried to throw him off the cliff, but he got hold of both of them and jumped off the cliff with them. He landed on a ledge but the two young men ended up going over. Yamǫga turned himself to stone, and it can still be seen today. Below him are two trees. These are said to be the boys that fell off with him. Sahtu Heritage Places and Sites Joint Working Group, Rakekée Gok’é Godi: Places We Take Care Of.

Norman Wells Traditional Place Names map

[ Sahtu Atlas Table of Contents ]

[ Next Section ]

Phone: 867-374-4040

Phone: 867-374-4040 Email:

Email: