Communities Of The Sahtu

I live in the Northwest Territories, in a little town called Fort Good Hope, down the Mackenzie River... I have lived here for thirteen years. Every year I go to fish camp with my grandparents. I've learned a lot from them, such as traditional ways, making dry meat and dry fish, snowshoes, trapping, and other stuff...

I learned a lot from my grandparents, so now I know how to do stuff on the land. Lorraine Gardebois, Fort Good Hope, 2001

The Sahtu communities are all founded in the resource industry, but retain traces of their original frontier character. The four Dene communities were originally established as centres in the fur trade. The economy of Norman Wells is still based on the oil resource that first gave rise to the community. Local economies have more recently diversified and evolved as administrative centres for social services and land claims implementation, including resource management functions.

The communities have modernized considerably over the past several decades, and now boast water delivery, cable television, regular air service and winter road access.

Today, the population of the Sahtu is over 2,800 and is projected to exceed 3,000 by the year 2019. The diversity of the population reflects the changes that have taken place over the past century. As of the 2001 federal census, the Sahtu Dene comprise 71% of the total population; 7% are Métis, 1% are Inuit, and 21% are non-aboriginal. A large proportion of the population, almost 40%, is under the age of 25. The creation of a viable future for these youth in the region is a major focus of Sahtu leaders as they move toward greater control of resources and services.

Transportation

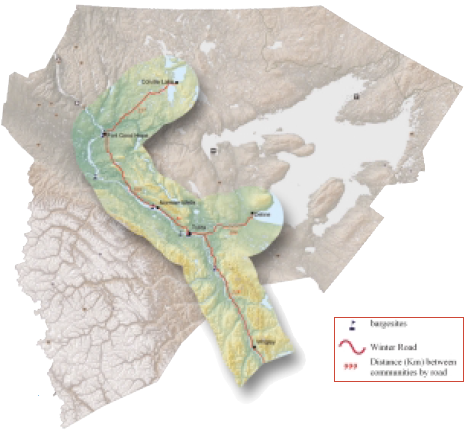

Like much of Northern Canada, the Sahtu and its communities cannot be accessed by southern methods of transportation such as all-season roads or railways. Inhabitants rely on year-round air transport, summer river barge service and ice roads in the winter to move around the Region and to ship supplies and goods.

Barges

From mid-June to mid-October, high power tug boats launch from Hay River push specially designed flat-bottom barges up and down the Mackenzie River, delivering boats, cars, snowmobiles, heavy equipment, fuel oils, building supplies, bulk foods and other goods.

Service was originally provided by private barge companies hired by the Canadian government. Eventually competition reduced the barge companies to the single, government-owned Northern Transportation Company, Ltd (NTC). In the 1970s, as part of their land claims settlement, the Inuit became owners of the NTC's large fleet of tugs and barges.

The Mackenzie River demands expert navigational skills from the tug boat crews. The river's annual freeze up and sudden flood of water and ice scours the river bottom, changing the navigation channel from season to season. Coast Guard crews patrol the river, measuring depth using electronic depth sounders, then anchoring buoys to mark the channels for the barges.

Winter Roads

Winter roads usually open mid-to-late December and operate through mid-March. Freeze-up provides a bed of frozen ground and a coat of ice on the lakes, thick enough to allow the weight of vehicle traffic. The winter road is cleared and maintained from the termination of the permanent highway at Wrigley up along the Mackenzie Valley with an extension near Tulita going east to Deline and an extension at Fort Good Hope travelling east to Colville Lake.

For the communities along the Mackenzie River, the winter road replaces summer barge service with truck service. For Deline and Colville Lake, which do not have access to barge service in the summer, the winter road is critical for the delivery of bulk supplies such as heating fuel, electricity and other necessary goods not practical or possible to be delivered by air.

Climate and terrain challenge transportation to the Sahtu and within the region

[ Sahtu Atlas Table of Contents ]

[ Next Section ]

Phone: 867-374-4040

Phone: 867-374-4040 Email:

Email: