Introduction

The Sahtu Region is a place rich in cultural heritage, breathtaking landscapes and natural resources. The maps in this atlas help reveal much of its wonder. There are recent maps of the Sahtu that represent ongoing scientific research, specializing in natural history, including climate, ecology, wildlife and resource distribution. Other maps show the Region’s modern infrastructure: its roads, seismic lines and pipelines. Even the boundary map, a patchwork of political and property boundaries defining Aboriginal, Crown, and Territorial jurisdictions is relatively new, created with the signing of the Sahtu Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement in 1993.

These maps are in contrast to the traditional mapping of the original inhabitants of this land, the Dene. A fine mesh of trails over centuries of use traces a relationship with a territory that once knew no boundaries. This map shows the land to be animated by the Dene. They travel across the land. They know it, they name it. In the words of Dene researcher Phoebe Nahanni, “We have our own place names for all our camps, for the lakes, the rivers, the mountains – indicating that we know the topography of our land intimately” (from Watkins, 1977).

For the Dene of the Sahtu, the land is mapped in words. The Dene place names spread across the landscape are linked to a multitude of ancient stories that bind the people to the land in a way that is more than purely functional. The land becomes a representation of Dene history and spirituality since time immemorial, and patterns of land use and travel identify what it means to be Dene. Knowledge and skills evolved over generations for survival in a harsh climate are linked to an ongoing sense of responsibility in taking care of the land.

Since the days of the fur trade, the Dene have shared this land with their Métis relatives and neighbours. The Dene and Métis continue to maintain land based subsistence practices, but land use and mapping are now influenced by new factors. The sinuous traditional trail system has been overlaid with rectilinear seismic lines and the straight lines of political jurisdictions. Recent maps reflect conflicting visions for development and conservation of natural resources.

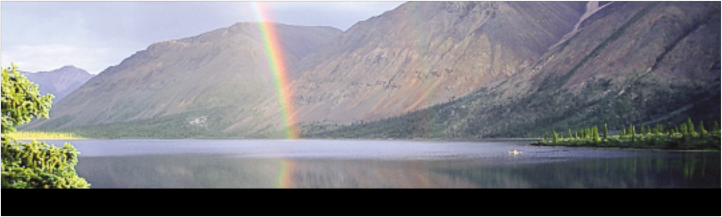

Methods of map making have also changed. The maps in this atlas are the product of sophisticated Geographic Information System technology, providing colourful bird’s-eye views of the land. But to truly know the Sahtu we still must walk the land, ride the rivers, learn and tell the stories.

Over the past decade, the Sahtu has become renowned as a centre for Dene and Métis cultural revitalisation and research, for its internationally significant conservation areas, and as a zone of intensive petroleum and mineral exploration and development. In bringing together stories and maps, this book reveals the key challenge of the current period in the Sahtu – that of balancing pressures for development and modernization with the values of environmental conservation, and preserving the access of the Dene and Métis to their cultural heritage on the land.

“Good quality maps can be used in support of many diverse projects such as: documenting traditional knowledge, determining shared use areas and reconciling conflicts, supporting compensation claims, negotiating co-management agreements, determining environmental impacts of development, negotiating protection and benefits from development, administrating land use permits, providing baseline data for community planning and resource management, developing education curricula.” - from original Sahtu Atlas proposal, 2001

[ Sahtu Atlas Table of Contents ]

[ Next Section ]

Phone: 867-374-4040

Phone: 867-374-4040 Email:

Email: